|

|||

PaperThe Development of Professional Developers: Learning to Assist Teachers in New Settings in New Ways

More than at any time in recent history, teachers’ professional development is being viewed as the key ingredient in improving U.S. schools (Sykes & Darling-Hammond, 1999). The perceived importance of professional development is directly related to the ambitious nature of the reform goals and standards that have been put into place over the past decade by various subject-matter organizations (e.g., National Council of Teachers of Mathematics [NCTM], 1989), state education departments, and professional boards (e.g., National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, 1989). It is now widely accepted that meeting these goals and standards will require a great deal of learning on the part of practicing teachers, the vast majority of whom were taught and learned to teach under a different paradigm of instruction and learning. The kind of learning that will be required has been described as transformative, that is, as requiring wholesale changes in deeply held beliefs, knowledge, and habits of practice (Thompson & Zeuli, 1999). In this article, we identify and describe the challenges that teacher educators and professional developers are likely to encounter as they design and implement new programs to help teachers as they undergo this transformative change. Just as teachers will need to relearn their practice, so will experienced professional developers need to relearn their craft, which traditionally has been defined as providing courses, workshops, and seminars. Although much has been written about the magnitude of the shift that teachers will have to make, we know little about the changes that are required of professional developers as they make their practices more responsive to the demands of the current reform era (Wilson & Ball, 1996). The article has four sections. First, we describe the forms of professional development that currently exist in the United States and contrast them with emerging ideas about how professional development should ideally be constituted to support teachers effectively in the new reforms. Then we present two cases of professional developers who engaged in long-term efforts to work with teachers in new ways, identifying the challenges that each developer faced. In the final sections, we compare and contrast these challenges and then discuss the broader implications of our work.

Professional Development: What We Have and What We Need For most teachers in the United States, support for instruction improvement takes two broad forms: mandated district-sponsored staff development, and elective participation in courses, workshops, and summer institutes, often provided by university-based teacher educators. These forms of professional development were designed to support a paradigm of teaching and learning in which students’ roles consisted of practicing and memorizing straightforward facts and skills, and teachers’ roles consisted of demonstrating procedures, assigning tasks, and grading students. Neither form was designed to support the deepseated reexamination, ongoing experimentation, and critical reflection that are required to develop the beliefs, knowledge, and habits of practice that undergird the complex forms of teaching recommended by current reforms. District-sponsored staff development typically consists of a menu of training options (workshops, special courses, or in-service days) designed to transmit a specific set of ideas, techniques, or materials to teachers (Little, 1993). For example, teachers may be asked to select a workshop from a list of options that includes training on the use of manipulatives, how to implement cooperative learning groups, or assertive discipline techniques. Such approaches treat teaching as routine and technical (Little, 1993) and encourage tinkering around the edges of practice rather than totally overhauling it (Huberman, 1993). In addition, they offer teachers only limited access to intellectual resources outside the teaching community and present few opportunities for meaningful collegial interactions within the community (Little, 1993). Courses given by university-based teacher educators are usually associated with graduate degree programs and often have an academic rather than an applied focus. Although workshops and summer institutes sponsored by these educators are often more oriented to practice, they generally lack follow-up support for implementation. Like district staff development, these one-time sessions or even two-week institutes seldom consider the positive and negative factors within the school environments to which teachers return. In addition, both district staff development and university-sponsored workshops and courses are usually planned by people other than those for whom the professional development is intended (Fullan, 1991). Overall, both of these types of professional development generally result in a disconnected and decontextualized set of experiences from which teachers may derive additive benefits, that is, the addition of new skills to their existing repertoires. However, the design and characteristics of these forms of professional development make it highly unlikely that teachers’ practices will be transformed by these experiences.

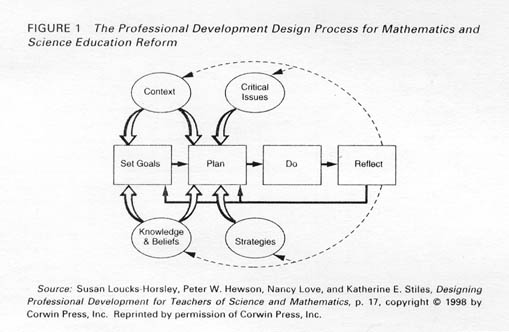

A New Paradigm for Professional Development The outlines of a new paradigm for teacher professional development are beginning to emerge (Ball & Cohen, 1999; Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 1995; Little, 1993; Loucks-Horsley, 1995). Based on a sober appraisal of the depth of relearning required of teachers and an honest assessment of what has not worked in the past, the new paradigm encompasses the following features: Teacher Assistance Embedded in or Directly Related to the Work of Teaching Teachers need assistance that focuses on their day-to-day efforts to teach in these new and demanding ways. Such assistance is best provided by support directly focused on an individual teacher’s practice, such as coteaching, coaching, assistance with planning, and reflecting on actual lessons (Schifter & Fosnot, 1993), or by guided group discussions surrounding selected authentic artifacts from practice, such as student work, instructional tasks, and cases of instructional practice written by and for teachers (Ball & Cohen, 1999). Both forms of assistance aim to stimulate teacher reflection on their current practice in light of new goals for student understanding so as to enhance teacher-planning and decisionmaking processes. Teacher Assistance Grounded in the Content of Teaching and Learning A characteristic of new calls for reform is their focus on meeting high standards associated with the major school subjects (Little, 1993). Traditional forms of staff development tend to focus on topics such as cooperative group learning that do not effectively help teachers learn how to orchestrate learning experiences that develop students’ understanding of important disciplinary concepts. Teachers frequently need to encounter the discipline as learners themselves, before grappling with how to teach it (Ball, 1991). Professional development should give them the opportunity to do so, as well as scaffolding the ongoing development of content knowledge as they teach. Development of Teacher Communities of Professional Practice The new paradigm for professional development encourages collegiality among teachers to counter the isolation typical of teaching. Calls for school-wide reform have meant that professional developers must adjust their frames of reference from working with individual teachers to working with organizationally intact groups of teachers. As a result, a new set of goals has been placed under the purview of professional development, including community building; the development of teachers’ capacities to explain, challenge, and critique the work of peers (Lord, 1994); and the development of teacher leaders (Lieberman, Saxl, & Miles, 1988). Collaboration with Experts Outside the Teaching Community Teachers cannot be expected to be knowledgeable about all aspects of school reform, subject-matter standards, or professional practice. Thus, collaboration with knowledgeable sources outside a teacher’s immediate circle is crucial. Outside experts — often university-based educators — bring fresh perspectives, ideas about what has proven successful elsewhere, and an analytic stance toward the school improvement process (Little, 1993). The key is establishing trusting relationships between practitioners and outside experts in which they work together on problems of practice by bringing different kinds of expertise to the table. Consideration of Organizational Context Teachers perform their work within multiple contexts, including schools, districts, communities, and states; the values and established procedures of each have an impact on classroom practice. Professional developers must carefully analyze the constraints and alternatives offered by each of these various contexts, ranging from the unwritten cultural norms to explicit regulations and policies. To accomplish this goal, professional developers need to join with administrators and other policymakers to establish alignments among these contexts. Such alignments will bring coherence to teachers’ professional development experiences and will ensure that these experiences are supported by organizational values and operating procedures (Elmore & Burney, 1997). The above paragraphs offer an overview of features that characterize the emerging paradigm of professional development that seeks to transform teachers’ beliefs, knowledge, and habits of practice. Susan Loucks-Horsley, Peter Hewson, Nancy Love, and Katherine Stiles (1998) offer a complementary perspective on the new paradigm by proposing that the process of teacher assistance is best conceived of as a design process. They maintain that effective professional development is not about importing models or following formulas, but rather about thoughtful, conscious decisionmaking. It is about creating, implementing, reflecting on, and modifying approaches and programs.  As shown in Figure 1 (p. 242), the centerpiece of this process is a planning sequence that incorporates goal setting, planning, doing, and reflecting. Feeding into the process is the designers’ repertoire of professional development strategies; their knowledge and beliefs about teacher learning and the change process; their consideration of the context within which the professional development and teacher learning will occur; and, finally, their attention to the critical issues that influence the long-term success of a professional development plan, such as leadership, capacity building for sustainability, and professional culture. Although the professional development design framework shown in Figure 1 was developed with mathematics and science teachers in mind, it incorporates insights from many fields of inquiry: school change, staff development, and institutional organization and educational leadership, as well as research on the teaching and learning of mathematics and science. In the past, professional development has been defined separately by each of these areas without recognition of potential interface with the others. For example, subject-matter specialists typically design professional development that focuses on content issues with little or no attention to organizational context; educational leadership specialists, on the other hand, tend to focus on organizational issues with little attention to subject matter. New approaches to professional development must reach across these boundaries to provide assistance that is both transformative for teachers and that encourages the development of school cultures congenial to the ongoing refinement of teachers’ newly learned knowledge and skills. Research on Enactment of the New Paradigm Few, if any, detailed studies exist of long-term, comprehensive efforts to develop and enact professional development programs that can support more complex forms of teaching (Little, 1993; Sparks & Loucks-Horsley, 1990). The few studies that do exist focus on teachers and the changes they must undergo in order to participate more productively in these new forms of professional development (see, for example, Schifter & Fosnot, 1993; Stocks & Schofield, 1997). Research suggests that teachers who are accustomed to workshops that feature lectures and "take-away" materials for tomorrow’s lesson frequently feel uneasy when asked to coconstruct a plan for long-term collaborative work with outsiders. They feel unsure of the usefulness of time spent relearning subject matter and, when given shared planning time to work with colleagues, do not know how to use it productively. Conspicuously missing from this work is research on how professional developers themselves must change to enact these new, more complex forms of teacher assistance (Wilson & Ball, 1996). We know little about the challenges that individuals accustomed to providing one-time workshops or university-based courses will encounter as they attempt to transform their practice to become more responsive to the new demands. (1) The lack of scholarship in this area leaves us with no direct guidance as to how to frame studies of the development of professional developers. Thus, without information on the learning trajectories of teacher educators, we might turn to what is known about the learning of teachers in the context of the current reforms. Studies of teacher learning suggest that teachers interpret new ideas and practices through the lens of their existing beliefs and habits of practice (Cohen & Ball, 1990). Teachers filter information about new ways of teaching through their prior knowledge of being a student in K-12 classrooms (Ball, 1990), as well as through cultural images of what teaching should look like (Stigler & Hiebert, 1998). In fact, it has been argued that teachers’ prior knowledge and experiences assume greater weight, given the lack of widely shared visions of what the new teaching practices would look like if well enacted. Without specifications of the model they are aiming for, teachers naturally fill in the gray areas with knowledge from their past experiences. Based on similarities between the task of transforming one’s teaching practice and the task of transforming the practice of professional development, one might expect that professional developers would also interpret the new calls for reform through the lens of prior knowledge and experiences. Given that the new paradigm for professional development is not clearly specified or widely shared, we can expect professional developers to fill in the gray areas based on their existing understandings and practice.  Table 1 (p. 244) highlights the discontinuities between the old and new paradigms for professional development using the inputs to the design process (as described by Loucks-Horsley et al., 1998) as an organizing device. A scan of the table suggests that the recommended shifts are quite extensive. They require professional developers to become immersed in the actual settings in which their clients do their work, to be willing to examine firsthand the impact of their efforts on teachers’ practice and student learning, and to hold themselves responsible for the successful implementation of an instructional program by a cohesive group of teachers, not simply the development of teachers as individuals.

Two Cases of Professional Developers In this article, we further illuminate the nature of the shifts required by describing two cases of professional development design and enactment. Specifically, we examine the thinking and actions of four university-based educators in two different settings during multiyear excursions into this new world of professional development. Because these educators’ prior practices were fairly typical of the modal form of professional development in the United States today, we believe that a cogent, empirically based description of their journey will be useful to others who travel this path in the future and to those who study professional development. Context of Our Cases The setting of our cases is a national, multiyear mathematics reform project, Quantitative Understanding: Amplifying Student Achievement and Reasoning (QUASAR). This project fostered and studied the development and implementation of enhanced mathematics programs for the students attending middle schools in disadvantaged communities (Silver & Stein, 1996). The mathematics instructional programs were aimed at encouraging the development of complex forms of thinking, reasoning, problem-solving, and communication compatible with the vision portrayed in the Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for School Mathematics (NCTM, 1989). (2) Since the vast majority of QUASAR teachers were elementary certified and had studied little mathematics, the project posited that teachers would need sustained support and intellectual guidance from knowledgeable professionals who could enhance their general understanding of mathematics content and pedagogy. In QUASAR, "resource partners" (typically university-based mathematics teacher educators) performed this function. The resource partners provided expertise about mathematics, mathematics teaching and learning, teacher education, and other areas critical to the support of instructional reform. They were expected to work collaboratively with all of the mathematics teachers in a given middle school for the duration of the five-year project. From the outset, resource partners were viewed as critical agents for teacher professional development. Moreover, the role of the resource partners, as explicated in the QUASAR Project design, approximated the new paradigm for professional development discussed in the beginning of this article. For example, resource partners were expected to use a variety of formats, including the provision of in-class support, and they were expected to attend to school context issues. Features such as these provided a broad outline of what was expected; the details of what constituted effective teacher support were expected to be filled in by the resource partners and teachers working together to create new forms of collaboration. We selected the particular resource partners who are the focus of this article because of the longevity of their service to the project and their readiness and ability to talk articulately about their work. Although all had been successful in traditional teacher education settings, such as university coursework, student teaching supervision, workshops, and summer institutes, this was their first experience with school-based professional development. As such, their backgrounds and prior experiences were typical of U.S. professional educators at the time, although the roles and challenges they were taking on were extremely forward looking. By working with teachers in their setting nine years ago, the QUASAR resource partners were pioneers in this new model of professional development. The resource partners collaborated with teachers in two different middle schools, both of which were located in urban school districts. The first, Riverside Middle School, serves a socioeconimically and ethnically diverse student population. (3) The second, Franklin Middle School, is a high-poverty, ethnically and linguistically diverse school in one of the twenty-five largest urban school districts in the country. In both school settings, the resource partners and teachers formed partnerships and then applied — as a collaboration — to become part of the QUASAR Project. The approaches to professional development and collaboration taken in each of these sites provide an interesting set of contrasts. Data Sources and Analysis The two cases draw from a range of data sources from the QUASAR Project documentation archives, including the sites’ initial proposals for QUASAR funding; annual reports prepared by each site to describe plans for the upcoming year and to provide a summary of the previous year’s accomplishments; transcripts or summaries of regularly scheduled interviews conducted with teachers and resource partners; artifacts from professional development activities (e.g., videotapes, agendas, summaries, materials); curricular materials; and a summary of professional development that synthesized available data over the five-year period. An additional source of data was a set of interviews conducted during the spring of 1997 with key members of the Riverside and Franklin teams — the two main resource partners (one from each site) and three teachers from Riverside. These interviews allowed individuals to reflect on their decision-making process during the project. Data analysis occurred in two phases. First, from the above data, we created a portrait of each school that described the form and substance of professional development in each of the five project years. Tables were then developed that highlighted the changes in professional development over time and made it possible to identify critical points in the evolution of professional development (that is, times when changes occurred in the kind of support provided). For each site, two time points — summer 1990 and summer 1993 — were identified. Second, we analyzed the professional development decisionmaking processes at these two time points using the professional development design framework (Loucks-Horsley et al., 1998). As noted earlier, this framework proposes a process by which exemplary professional development programs in mathematics and science are created, implemented, and modified. Using it as an analytic guide enabled us to compare the thoughts, words, and actions of the resource partners with features of the new paradigm, thereby identifying aspects of their practice that were compatible or incompatible with it, as well as those that appeared absent from the resource partners’ repertoire. "Freezing" the design action at the two points in time enabled us to identify differences in the resource partners’ goals and plans between the beginning and midpoints of the project and to connect the changes to their reflections on their efforts, as well as to changes in the context and in their knowledge and beliefs. Riverside Middle School During the 1989-1990 school year, Marcia Evans, a university-based mathematics teacher educator, and Michele Gardner, a university-based curriculum developer, approached teachers at Riverside Middle School to ask them if they would like to participate in a schoolwide implementation of Visual Mathematics (VM), an NSF-supported curriculum that was in the process of being developed by Gardner. At the time, a respected teacher at Riverside was already implementing the VM curriculum in his sixth-grade mathematics classes. The other mathematics teachers at Riverside were impressed with what they had seen. They believed that the VM curriculum would positively influence students’ mathematics achievement and attitudes toward the subject and better prepare them for more challenging mathematics coursework at the high school level and beyond. Therefore, the Riverside teachers enthusiastically agreed to participate in writing a QUASAR Project proposal to support their efforts to implement a new curriculum. From the beginning, the goals of the Riverside teachers and resource partners revolved around the VM curriculum (Bennett & Foreman, 1991). Unlike traditional textbook curricula, the VM curriculum is comprised of complex tasks that cannot be solved by application of a single algorithm and often require a written explanation of how the problem was solved. The stated goal of VM for students was "to develop better conceptual understanding of fundamental concepts in mathematics and to be able to use this understanding to explore and resolve challenging problems" (from the initial funding application, spring 1990). Learning how to effectively implement this curriculum was the implicit goal for teachers. The resource partners believed that this curriculum could be used as a scaffold for teacher learning and as a basis for their professional development experiences. In their judgment, careful use of the VM curriculum would enable teachers to appreciate the underlying coherence in the conceptual development of mathematical ideas. Moreover, the curriculum supported teacher learning by providing rationales for why certain tasks were used to introduce specific concepts, along with an overview of possible student responses to the tasks and suggestions regarding how the teacher might deal with these responses. Teachers were required to take a 60-hour summer introductory course about the mathematical ideas underlying the VM curriculum, as well as a 30-hour summer course on implementing VM. These courses gave teachers the opportunity to explore the tasks in the curriculum as learners and to reflect on the implications of their experiences for their teaching of the curriculum. According to Gardner, this experience "gave them powerful personal experience [and] in the process of exploring the mathematics, they would become more attuned to their own learning processes and therefore be better able to think about how kids learn" (Interview, June 1997). Monthly full-day sessions provided the primary support for Riverside teachers during the project’s first three years. These sessions offered teachers experiences intended to expand their view of mathematics teaching and learning (e.g., articles to read, instructional tasks to solve, ideas to consider). During each session, time was also allotted for teachers to reflect on their own practice (using videos, student work, teacher journals) in light of their new experiences. Believing that growth occurs as a result of teachers’ being confronted with a conflict between new ideas and their existing beliefs and/or practices, the resource partners reasoned that these sessions would create disequilibrium for teachers and serve as the impetus for constructing new practices. During the first three years of the project (fall 1990-spring 1993), the professional development plan, as designed by the resource partners, was implemented as intended. Teachers participated in all the activities with considerable enthusiasm, especially for the first two years. They used the VM curriculum in their classrooms as the basis for instruction, implementing it in both form and spirit. Routine tasks were replaced with cognitively challenging tasks, silence was replaced by student explanations and mathematical argumentation, and students were grappling with important mathematical ideas and concepts (Smith, 1997). Moreover, student-level data showed growth from fall to spring in the students’ ability to think, reason, solve problems, and communicate mathematically (Lane, 1993; Lane & Silver, 1994). (4) In addition to improved teaching and student learning outcomes, over the three years the teachers grew together as a community of practice (Stein, Silver, & Smith, 1998). As a result of time spent together in meetings, as well as informal "tagging up" between classes, the teachers learned to trust and respect one another’s contributions to their shared goal. The growth of a stable teacher community was aided by consistent and supportive school leadership, which was made possible by the fact that the same principal remained throughout the project. The three new teachers who were hired during this time were welcomed and mentored by the "old-timers" and gradually assumed their place as contributing members of the community. As the teachers grew into a teacher community, however, they also grew apart from the resource partners. By the third year, their growing dissatisfaction with the professional development program threatened the collaboration. The Turning Point At the end of the third year of the project, Marcia Evans accepted a position in another state, thus making it impossible to continue in the role of resource partner. At the same time, the Riverside teachers told Michele Gardner that they planned to take charge of the nature and direction of their own professional development. They no longer wanted to attend meetings designed and facilitated by someone else. As one teacher commented: You know, eventually the group wants to be independent. They want to kind of strike out on their own in their own direction and o whatever they want to do. You know it’s a very long process of development. And I think that sometimes we felt like no one was willing to let go. (Interview, Teacher A, June 1997) The teachers designed the professional development plan for the project’s final two years with limited input from Gardner. It differed dramatically from earlier plans and focused more directly on their work at Riverside. In particular, it provided time for teachers to meet together often — twelve three-hour after-school meetings — to deal with three identified issues: assessing and reporting student learning, implementing the curriculum across grade levels, and involving parents. The resource partners participated "by invitation only," with teachers dictating the limits of their involvement. Many of the activities that had characterized the work of professional development during the first three years, most notably the full-day sessions, were eliminated or changed. These changes represented radical revolutionary changes rather than subtle evolutionary modifications to the existing plan. The redesigned professional development plan differed dramatically with respect to the form and substance of the activities, the roles of the teachers and resource partners in the creation and implementation of the plan, and the rationale that undergirded the plan. With respect to form and substance, the new plan shifted the predominant format from off-site workshops to after-school meetings and from teachers’ grappling with issues of personal development to the group’s grappling with issues associated with implementing VM at Riverside. The teachers were adamant that reflection not be the central focus of professional development activities in years four and five. According to the teachers, reflection "had been done to death" during the first three years of the project and was no longer needed. Instead, the teachers chose to focus on the pragmatics of day-to-day implementation in their local school context. With respect to roles, the new professional development plan shifted control of the decisionmaking process from the resource partners to the teachers. Finally, with respect to rationale, the new plan reflected a shift from a plan based on an articulated theory of teacher learning to one that developed in response to teachers’ own articulated needs. Challenges Faced by Resource Partners at Riverside The story behind these radical changes comprises a series of challenges faced when the resource partners took on new forms of responsibility in this school-based reform project. The work with Riverside teachers represented the resource partners’ first attempt at schoolwide implementation of VM. Their prior work had prepared them for the difficult task of transforming teachers’ orientation toward mathematics and how it should be taught and learned. However, it was less helpful in preparing them for the need to stretch beyond issues of subject matter and teacher learning into the realm of school context and culture. Strategies The resource partners’ main professional development strategy was to build teacher capacity of high-level instruction through immersion in mathematics — which took place during the initial summer workshop — followed by curriculum implementation and reflection on practice during the school year. Although not usually recognized as a professional development strategy per se, the resource partners skillfully used the VM curriculum, in tandem with guided reflection, to provide a scaffold for ongoing teacher learning of both subject matter and new forms of pedagogy. Despite its success in developing teachers’ understanding of mathematics and their ability to guide students’ development of concepts, the original professional development plan lacked a crucial element of the new paradigm: a direct response to the teachers’ expressed need for the resource partners to visit their school more frequently to observe and teach in their classrooms. By choosing not to observe or teach in the teachers’ classrooms, the resource partners deprived themselves of the opportunity to appreciate more deeply what it was like to implement the VM curriculum specifically in Riverside classrooms with Riverside students. Ultimately, the negative signals sent by their lack of attention to teachers’ experiences at Riverside negated the goodwill that had been established in earlier phases of the collaboration. Although the teachers continued to implement VM, future collaboration between the resource partners and Riverside teachers was never the same. Indeed the collaboration in which the teachers and resource partners found themselves was more extensive, long term, and personally demanding than any semester-long course or three-week institute with which they had been involved in the past. It is not clear that either party explicitly thought about the nature of the commitments they were making at the beginning of the project. However, in a reflective interview at the end of the project, Gardner drew comparisons between the interpersonal demands of older models of teacher education and those of her involvement with the Riverside teachers. She commented that a teacher who was taking a course might think, "This is one term. I can put up with whatever. I don’t agree with this, but, oh well, I’ll ignore it for a term and do what I need to do." She went on to contrast this with the implications of a long-term relationship for the teachers who participated in this project: When you get the commitment to work with somebody for five years, you have to work though all those little things. You can’t let something just sit that’s really troubling you. And those things that you do just let sit are at the surface. No matter what you do, eventually they’ll surface … and they’ll probably surface in a much uglier way than if you would have dealt with it in the first place. By the end of the project, Gardner was keenly aware of the ways in which the commitments required by this kind of work extended into the realm of interpersonal relationships between the resource partners and the teachers. This demand to transcend boundaries normally associated with shorter term commitments clearly points to the need for new models of relationships that balance the interpersonal and the professional. Knowledge and Beliefs A huge issue at Riverside was, Who sets the agenda? At no point in the project did decisions regarding professional development reflect the perspectives of both the resource partners and the teachers. Initially, teachers were not concerned about their lack of input into the professional development design. They viewed the resource partners as the experts in the curriculum and philosophy that formed the basis of their reform efforts. However, as the teachers gained experience and confidence with the new curriculum and pedagogy, they were better able to articulate their needs. Over time, the teachers came to believe that the resource partners did not take these needs into consideration. The battle line over agenda setting was drawn with respect to the full-day sessions. By the third year, the teachers were reluctant to have the resource partners continue to set the agenda because they did not want to sign up for more "education philosophy and that kind of thing." Teachers felt that the full-day sessions were critical during the first two years. Over time, however, they felt that these full-day sessions (i.e., critiquing videotapes of practice, reading research articles, reviewing student work) were too abstract or "philosophical" and disconnected from day-to-day issues of implementing the curriculum in their classrooms and schools. As one teacher stated: We needed the staff development that we had at the beginning. It was absolutely critical. And I think had that not happened, we wouldn’t have been as successful. But the thing I’m pointing to is to where our needs began to change a little bit. We were still back doing more of that other stuff, and we just didn’t see that as big enough. I think one point for staff developers to realize in the future is that there comes a point, especially in a long-term thing like this, that you let your teachers go to do their thing. You just [need to] be there to support them. You … back off a little bit. (Interview, Teacher A, June 1997) After several months of trying (unsuccessfully) to influence the agendas of those meetings, the teachers felt that the "playing field was not level" and that the expertise they brought to the endeavor was not valued by the resource partners. The resource partners were unwilling to change the nature of the full-day meetings because they believed the teachers needed to continue to reflect on their practice and to experience disequilibrium in order to continue to develop professionally. By opting out of these sessions, the resource partners claimed, teachers were avoiding confronting issues of practice that still needed to be resolved. While Gardner’s assessment may have been correct, her inflexibility on the issue of agenda setting ultimately left her with no voice in planning professional development for the fourth and fifth year of the project. The perception on both sides that they could not codesign a plan led the teachers to completely take over their professional development for the final two years of the project. This takeover cast into stark relief the differences between the plans in terms of goals and underlying theoretical foundations. While the resource partners’ plan was based on a clearer set of goals and rested on a firm foundation of learning theory, the teachers’ plan pointed to a critical and unaddressed need: supporting the continuous learning of teachers within the organizational framework of their school. Although the teachers did not have an elegant theory undergirding their plan, the topics identified for "work" (i.e., assessing and reporting on student learning, articulating and implementing the curriculum across grade levels [including elementary and high school], and dealing with parents) suggested that the teachers felt a need to situate their ongoing development within the expectations and structures of the institution in which they were teaching. In order to meet the goal of the project for schoolwide institutionalization of mathematics reform, the resource partners — whether they wanted to acknowledge it or not — needed to grapple with the issues raised by the teachers. To do so in a theoretically grounded manner would indicate the need for them to augment their theory of learning to include social and institutional factors that affect learning. Context At Riverside, the teachers felt that their personal experiences with their students in their school were not being heard. As the teachers gained experience with the curriculum, they made suggestions to the resource partners regarding how the materials might be modified to be more in-tune with their students’ needs. For example, the teachers felt that the reading level and complexity of directions presented challenges for their students that interfered with the mathematics learning; that the pacing was too fast; and that completing all the activities in any given unit was too time consuming. The resource partners responded simply that VM should be implemented in the same way and at the same pace for all students. Other teacher comments regarding weaknesses in the curriculum, such as a lack of real-world applications or absence of some content areas, were similarly dismissed by the resource partners. The teachers felt that the resource partners wold better understand the school context if they spent more time in their classrooms and actually taught their students. By all accounts the resource partners were rarely in the school, and almost never in the classrooms. As one teacher commented: They don’t need to come out here and observe, because if you observe, you just sit there … But if you teach it, you see where the kids are, you see why it takes so long to go with it, and you see the kinds of choices that are having to be made. I think, in order for them to truly understand where we come from, they need to see it [the curriculum] in the context where we’re teaching it … and maybe they would come out and they would find that, "Hey, keep going, you know, these kids are doing [it], they’re right where they’re supposed to be. It’s gonna work, keep going." … Because they have that experience to go from. (Interview, Teacher B, December 1990) The resource partners, however, did not see this as their role. From their perspective, their role was to support teachers in the implementation of VM by providing them with experiences outside of the classroom that would facilitate their growth and development. Therefore, in order to make appropriate decisions regarding experiences for teachers, the resource partners concentrated their efforts on understanding teacher thinking and classroom practices in a context-free manner. The information was gathered from watching videotapes of teachers’ classrooms, reading teachers’ journals, reviewing portfolios of student work, and talking with and listening to teachers and others who had visited the teachers’ classrooms, rather than by immersing themselves in the culture of the school and the particularities of each teacher’s classroom. And so, a standoff materialized: Riverside teachers felt that their knowledge of and experience with the students, the school, the environment, and the curriculum, as well as their concerns about the district and community, were ignored by the resource partners. The resource partners held firmly to their belief that the context in which teachers worked should not influence the kind of support they received. Critical Issues The adoption of the VM curriculum at Riverside Middle School was an important step toward building a coherent instructional program at the school. By providing a defined vision, a shared language, and a common set of instructional challenges and rewards, the curriculum was the fulcrum around which the teacher community formed in the early years of the project. Moreover, teachers’ participation in a common set of professional development activities during the first three years resulted in tremendous cohesion among members of the teacher community at Riverside. The solidarity of that community, along with the definition and structure of their practices, in turn supported the learning of new teachers and contributed to the blossoming intellectual identity of the Riverside mathematics faculty. However, in later years the teacher community did not continue to thrive. Although the original core of teachers did establish strong intellectual and personal bonds, after year three, new teachers did not enjoy the same access to a common set of activities that provided the scaffold for teacher learning during the early years. During years four and five, a structure developed whereby new teachers participated in monthly full-day sessions similar to those offered during the first three years of the project. It is important to note that these sessions did not include the teachers who were experienced in the VM curriculum. This led to a lack of opportunities for new teachers to become exposed to the values, language, and ways of interacting that were shared by the experienced teachers. As a result, the new teachers’ identities as contributing members of the community failed to develop. When the experienced teachers eventually left Riverside, there were no strong leaders in place who could provide support to incoming teachers or help create a sense of community and shared vision. Anecdotal evidence gathered during the sixth (1995-1996) and seventh (1996-1997) years of the project suggest that the new teachers lacked shared vision, had a less well-developed sense of and loyalty to project goals, were more tentative about implementing the curriculum, and, in general, were less motivated. Franklin Middle School The groundwork for collaboration between the resource partners and Franklin Middle School teachers was laid by a previous collaboration between Kenneth Newton, the primary resource partner, and two teachers from Franklin. These teachers had participated in a three-week summer workshop led by Newton to introduce teachers to the standards for school mathematics that had recently been published by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM, 1989). After hearing about the QUASAR Project, Newton asked his university colleague Randi Miller and the two Franklin teachers if they would be interested in submitting an application to become a QUASAR site. They expressed strong interest, and invited the principal of the school, the director of mathematics for the district, and the remaining thirteen teachers on the mathematics faculty to participate in the application and planning process. All participated eagerly, thus setting the stage for school-wide participation and districtwide support. Their initial goals were: 1) to deepen all students’ knowledge of mathematics and develop their higher order thinking skills; 2) to empower all teachers with the knowledge, motivation, support, and confidence needed to reform their practice; and 3) to develop and implement a middle school mathematics program that integrated problem-solving and proportional reasoning into all facets of the curriculum. The plan that was developed to meet these goals revolved around a set of activities designed to involve all teachers in the ongoing identification, development, and adaptation of challenging mathematical activities that could potentially enhance the existing curriculum. These activities were then to be implemented in teachers’ classrooms and subsequently discussed with colleagues in grade-level meetings. The teachers planned to keep detailed records of which activities worked and which did not, along with notes about modifications to the activities that were found to be useful. Then, during weekly grade-level meetings, summer workshops, and late-August planning sessions, the teachers and resource partners would assemble the activities into a year-long curriculum appropriate to each grade level. A second element of their plan focused on intensive work to identify ways in which proportional reasoning could be integrated with the main topics of their curriculum. The plan for professional development also involved regular interactions with teachers in schools during the workday. Newton planned to take a leave from the university during the first project year and to devote 50 percent of his time to the project. This would include two full days per week in the school, helping teachers to implement and evaluate curricular and pedagogical changes in their classrooms, attending grade-level meetings, and conducting before- and after-school workshops. In subsequent years, Newton’s total time commitment to the project would be reduced, but he would continue to spend a considerable proportion of his project time in the school and classrooms. During the first year, Miller planned to devote 20 percent of her time to the project. She would take the lead in helping teachers design, organize, and conduct research into the effectiveness of a unit on proportional reasoning. Undergirding this plan was Newton’s belief that the project’s success would be dependent upon establishing trusting and respectful relationships between the resource partners and the teachers. His intention was to spend lots of time in the school, getting to know the teachers, coming to understand their perspectives, and figuring out how to meld his agenda with their needs and desires. Another belief undergirding their plan was that teachers could and should be the agents of their own instructional redesign. More specifically, the resource partners believed that teachers should be responsible for developing instructional activities based on ideas and materials that were presented and discussed in group meetings. For example, when discussing his plans for the initial summer workshop, Newton stated that he would share materials from existing innovative middle school curriculum projects, resource books, professional journals, and software companies as a "starting framework" upon which teachers would develop their own activities. Similarly, when discussing the proportional reasoning strand of their work, Miller indicated that the goal was to equip teachers with sufficient mathematics content knowledge and knowledge of children’s thinking to develop their own materials for instruction and assessment. During large group sessions, the resource partners planned to model certain kinds of behavior — thinking, analyzing, questioning — that they expected teachers to gradually pick up and eventually perform independently. Thus, teachers would learn how to teach, the resource partners argued, by observing the resource partners as pedagogical models. The resource partners’ overall strategy for curriculum development and their beliefs that teachers could and would translate ideas learned in workshops into classroom activities are grounded in their prior knowledge and experiences. Newton’s summer institutes were typically built around a curriculum enhancement strategy whereby he helped teachers identify materials that could be used to supplement their basal textbooks. Miller’s prior experiences with the Cognitively Guided Instruction Project (CGI) were based on a particular professional development model that explicitly assumed that teachers would construct appropriate instructional activities after being exposed to research on how students learn particular mathematical topics. During the first three years of the project, all of the workshops, meetings, and classroom visits by the resource partners occurred as planned, in a good-faith effort to carry through with the professional development plan. Nevertheless, many of the project’s goals were not met. With respect to curriculum development, a complete and cohesive set of middle-grades curricular materials still did not exist at the end of year three. Although teachers experimented with many innovative classroom materials and discussed them in their grade-level meetings, they spent little time compiling the "better" activities into a meaningful curriculum. Thus, sifting through materials, organizing and placing them into a meaningful order, and adding information about how they were used — all essential pieces of creating a useful curriculum — were delayed until the summer months. A unit on proportional reasoning was developed in the first year, but no additional units were created in subsequent years. With respect to teacher development, teachers made some, but far from wholesale, changes in their practice (Stein, Grover, & Henningsen, 1996). In general, teachers learned to select and set up cognitively challenging instructional tasks but were less able to support their students’ thinking and reasoning in ways that maintained high levels of cognitive activity throughout the lesson. Finally, results on student learning were mixed. Although the students showed moderate gains on QUASAR’s measure of mathematical thinking, reasoning, and problem-solving (Lane & Silver, 1994), their scores remained flat on standardized, norm-referenced measures. By the project’s midpoint, the progress of Franklin was much more measured than the progress at Riverside. Without a guiding framework, teachers were struggling to develop a common voice, vision, and language. Although Newton observed classes on a regular basis, he was reluctant to comment critically on teachers’ pedagogical practices, thereby depriving them of the opportunity to learn how to reflect critically on their own practice. Finally, teachers’ translation of ideas about student understanding of proportional reasoning into meaningful instructional activities was hindered by a variety of factors. They had difficulty applying research on student learning conducted on non-Franklin students to Franklin students. It was difficult to codify student thinking in this domain in ways that made it amenable to devising instructional units or strategies, since the great diversity among middle school students’ understanding of this topic made it difficult to capture and address the various approaches that students could use to think about proportional reasoning problems. These difficulties contrast with earlier successful work that had been done in the primary grades in the CGI project. The limited successes at Franklin must be understood, however, against the backdrop of a school and district climate that was harsher than that at Riverside. The initial principal at Franklin, an extremely vocal supporter of the project, left within one month of her school’s selection as a QUASAR site. The individual who was hired to replace her supported the project, but in a more laissez-faire manner. He, too, was replaced in the third year of the project with yet another principal, who only modestly supported the project. Neither replacement principal had the leadership capabilities or commanded the degree of respect from teachers as the initial principal, whose departure represented a significant loss for the QUASAR Project. There was also a much higher rate of teacher turnover at Franklin than at Riverside. During the second and third years of the project, approximately 50 percent of the teachers were new to the mathematics department, due either to teachers’ leaving Franklin altogether or to the principal’s reassigning teachers. The teacher turnover was particularly exasperating to the resource partners because neither they nor the teachers had input into the selection process or into the assignment of mathematics teachers. The combined impact of principal and teacher turnover created a host of challenging conditions at Franklin. The recognition of these challenges led to changes to the professional development plan for the final two years of the project. A Redesigned Plan Unlike their initial plan, which was a widely shared document built by consensus, the plan for years four and five was developed by Newton and a small cadre of veteran teachers (resource partner Miller departed at the end of the third year). After Newton and the teachers designed the plan, it was reviewed and "approved" at a meeting of the entire mathematics department. The new plan retained the site’s focus on developing a curriculum that stressed problem-solving and wove proportional reasoning concepts throughout the curriculum; it stressed the articulation of this curriculum over the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades; and it included classroom observations by the resource partner. Once again, a variety of summer workshops and school-year meetings were planned. There were important differences, however, concerning how the work was to be accomplished, particularly with respect to the scope of teacher participation. In all respects of the planned work, the main activities were to be undertaken by a subset of teachers rather than by all fifteen teachers as called for at the beginning of the project. For example, a committee of five teachers who were all experienced with QUASAR was appointed to create the Franklin Curriculum Materials Book and a classroom assessment system. At the beginning of the project, all teachers were to be involved in the creation of classroom materials and the integration of these materials into a coherent curriculum. According to the new plan, the number of teachers involved in the intensive work on proportional reasoning diminished from all teachers to two teachers. Finally, at the midpoint, intensive classroom observations were planned on a regular basis only for the two teachers who would be carrying out the proportional reasoning work. The resource partner would observe and provide in-class assistance to other teachers as time permitted. Unlike Riverside, the changes at Franklin from the beginning to the midpoint of the project were more evolutionary than revolutionary. The substance of the plan, centered on teacher development of curriculum and the integration of proportional reasoning ideas throughout the middle school curriculum, remained the same. The collaboration among the cadre of veteran teachers at Franklin and the resource partner remained strong. Newton continued to empathize with their perspective; over his three-year involvement, knowledge that he gained of Franklin as a high-poverty urban middle school made him even more sympathetic to the constraints under which these teachers worked. The biggest change of the project occurred with respect to Newton’s knowledge and beliefs about how teachers learn and successfully change their practice. By the project’s midpoint, he no longer believed that ideas discussed in meetings and workshops were easily translated into instructional practice. Faced with mounting evidence that the Franklin teachers were not applying what was discussed in grade-level meetings and workshops to their practice, he began to revise his ideas about how long and how intensively he would need to work with teachers to affect their knowledge, beliefs, and habits of practice. Newton also began to see that most teachers were underprepared and too overwhelmed for the task of developing curriculum. The above realizations occurred in the context of high teacher turnover, which resulted in a mathematics department with less consistency in terms of overall teacher commitment and motivation to the project. Taken together, all of these factors resulted in a conscious decision on Newton’s part to forgo intensively working with all teachers and instead to concentrate his efforts on a handful of committed veteran teachers. The story behind this shift comprises a summary of the challenges faced by the Franklin resource partners as they immersed themselves in an urban school context for the first time. Challenges Faced by Franklin Resource Partners The task of developing a middle school curriculum and transforming an entire mathematics faculty is daunting under any circumstances. In Franklin, the conditions of high poverty, student and staff transience, and limited administrative support added to the challenge. Although Newton was keenly aware of this context, he was ill equipped to address these challenges. Strategies The resource partners’ main professional development strategy to build teacher capacity for high-level instruction was the development and enhancement of curriculum. Like their counterparts in Riverside, the Franklin resource partners understood that the focus of their efforts had to go well beyond providing isolated take-away materials. As such, their goal was to develop teachers’ understanding of the content of the middle school mathematics curriculum, as well as ways to organize and teach that content. They hoped that, as teachers tried out the supplementary activities and replacement units in their classrooms and talked about them afterwards, they would learn new ways to think about mathematics and what counts as deep understanding of mathematics. Curriculum development did not turn out to be a viable strategy for professional development and Franklin. Teachers lacked the time, commitment, and content knowledge to evaluate new materials and to connect them to one another in a way that approached a meaningful, coherent, three-year curriculum. Moreover, there is little evidence that teachers’ subject-matter knowledge, beliefs, or habits of practice changed in fundamental ways by their curriculum development work. Without additional professional development that provided more structured opportunities to build teacher content knowledge and more critical feedback on their practice, curriculum development was simply a strategy not robust enough to transform teachers’ practices. (5) From the beginning, the Franklin resource partners used a variety of different formats for delivering professional development. Newton and Miller assisted teachers’ planning during grade-level meetings, regularly observed classes, and conversed informally with teacher between classes and before and after school. By participating in the ongoing daily lives of the Franklin teachers, Newton developed a deep knowledge of the conditions of their work, and he also earned their respect and loyalty. Unlike the Riverside resource partners, Newton appeared to understand from the outset that he was stepping into a long-term professional and interpersonal commitment that would be unlike any he had previously experienced. Indeed, his strong belief in the importance of relationship-building stemmed from this awareness. In the beginning, he spent many long hours listening to teachers and trying to understand their perspectives on what it was like to teach at Franklin. Although the trust he established would have allowed him to do so, he did not critically confront the teachers regarding their improvement efforts. Over time his views on the role of interpersonal relationships became more nuanced and elaborated. He began to believe that interpersonal good will represented only a small fraction of what it takes to create a successful program. At the project’s midpoint, he stated: What’s interesting here is that in spite of very good will on the part of a very united group of people at the beginning, and in spite of lots of support, these things still come out (that one is less broadly successful than was hoped for). I guess it shouldn’t be surprising, and yet in some ways Randi and I were surprised. (Interview, May 1993) The resource partners’ surprise that the reservoir of interpersonal trust and goodwill were not sufficient to overcome the challenges at Franklin was a hard and important lesson for them to learn. This realization opened the door for reflection regarding additional pieces of the interpersonal equation needed for success in building long-term, school-based relationships. Knowledge and Beliefs At Franklin, unlike at Riverside where the agenda setting switched hands from the resource partners to the teachers without a period of collaboration in between, agenda setting was always shared between the resource partner and the teachers. What did change in Franklin over time was the scope of teacher participation, from all teachers to a few who were experienced with QUASAR. Due to high turnover rates among teacher in the mathematics department, Newton and these experienced teachers felt that involving all teachers in coconstructing the professional development plan was not practical. In their opinion, the newer teachers would not be able to contribute meaningfully to the process because of their lack of experience and prior knowledge of the work at Franklin. During their work in Franklin, the resource partners needed to confront a major belief that undergirded their approach to teacher support. Eventually, they realized that the manner and ease with which knowledge and ideas learned in one setting (e.g., grade-level meetings, workshops) are translated into changes in instructional practice was far from trivial. In their previous experiences leading workshops and courses, the resource partners usually did not know if or how teachers used the new ideas in the classroom. At Franklin, however, they were confronted on a daily basis with discrepancies between what was discussed or modeled in group meetings and what actually unfolded in classroom lessons. As Miller noted: We had this vision that, in the beginning, that [sigh] sort of by our modeling things that we wanted the teachers to do, that they would learn how to do them … that they would become more reflective people and assume more of that kind of activity on their own. I don’t think that happened. I think that our plan was that we could get them started on this and then we could pull back and they would continually do it, but … I don’t see a lot of that happening with most of the teachers. (Interview, May, 1993) The lack of transfer between workshops and instructional practice can be traced to limitations in the framework underlying the resource partners’ initial plan. The most salient of these was the expectation that teachers would be able to recognize the usefulness of knowledge and skills learned in workshops and be able to access and use this knowledge at appropriate moments during the planning and delivery of lessons. The interactivity and competing goals that characterize classroom settings, however, made this transfer of knowledge a learning experience in and of itself. The resource partners were not prepared to scaffold this kind of teacher learning. Indeed, they had never had to do this in the past. Context At the beginning of the project, both resource partners knew intellectually that they were soon to face many challenges associated with an urban school context. However, they knew these challenges only in theoretical terms. For example, they were aware of the impoverished backgrounds of the vast majority of Franklin students but didn’t know how these students’ poor academic preparation would interact with the planned emphasis on complex mathematical thinking and reasoning. Similarly, the resource partners knew the level and kind of certification that each teacher possessed, but they had little understanding of these teachers’ capacities, subject-matter knowledge, and predispositions toward undertaking such a demanding instructional reform project. Finally, the resource partners knew that Franklin was in a large urban district, but they were unaware of the ways in which district practices for hiring teachers and reassigning administrators could impact their work. As a long-time resident of the city and an educator who had long been active in the public arena, Newton was aware of these factors and he knew they would matter. What he did not know was exactly how they would matter. Lacking experience in designing a long-term, school-based professional development plan, he immersed himself in the district context as a means of figuring out how context mattered for his work. Newton became a student of the harsh conditions at Franklin and, no doubt, his understanding of the obstacles to urban school reform increased greatly. But so did his pessimism about accomplishing mathematics reform in a system that consistently placed obstacles in his path. As Newton clearly indicated in one of his interviews, by the end of the third year, the resource partners had wearied of the successive waves of new mathematics teachers and had revised their expectations of what they felt was reasonable to accomplish: It comes down to — it’s like saying, "How do you get everybody in your class of seventh graders to be really excited about math?" And the answer is, "You don’t." What you can do is constantly try to motivate and try to steer and try to do the best you can. (Interview, May 1993) Reflecting on the first three years of the project, Newton noted that coming to grips with the realization that he could not make similar progress with all teachers was a very important lesson: I think our vision was that it would be more complete that it has been. We can look to both sides, we can look to the teachers and we can look to us and we can look to the plans and we can look to everything. And everything is under consideration. Ultimately it’s the reality of existence in a world that is trying to make change. (Interview, May 1993) Critical Issues It is ironic to note that, despite Newton’s attention to interpersonal relationships, a functioning community of practice that included all teachers of mathematics never existed at Franklin. Despite frequent social gatherings and good-natured interpersonal interactions, the development of a focused, professional learning community never gelled. Shared vision remained at superficial levels rather than deepening over time, a shared professional language and style of discourse never materialized, and new teachers had little in the way of an identifiable culture into which to be socialized. The handful of experienced teachers that emerged during the early years comprised a natural cohort of leaders. However, they became resentful of the energy and time required to bring new teachers on board. Instead of perfecting and honing their own skills, the experienced teachers were cast into the nearly full-time role of assisting successive waves of new teachers, many of whom were not highly motivated to participate in the project. The fact that the curriculum was underspecified made this task even more difficult. Without materials and/or any other formalized system for orienting new teachers, virtually everything needed to be continuously reinvested and transmitted through lengthy discussions in specially arranged meetings. In the later phases of the project, the more experienced and able teachers were recruited to design the curricular materials and assessment systems, while the less experienced teachers were asked to attend infrequent meetings and to implement what was designed by others. As in the later years in Riverside, the lack of participation in a common set of activities precluded the development of any sense of identity with or learning within a professional community of practice.